Working almost entirely with the colour white, the artist has for six decades created remarkably warm paintings in which the immaterial is made manifest

Hite, wassily kandinsky thought, had had a bad run in painting before him. The impressionists’ snow effects were usually rendered in light blue and mauve, while vincent van gogh, in an 1888 letter to his fellow painter émile bernard, wrote that he felt unjustified in painting with white – too far from nature, too far from the eyes. Only with the coming of abstraction, according to kandinsky, could white be asserted on its own terms. White is proper to abstraction, he claimed, because it comes from somewhere better than this fallen planet we inhabit: “this world is too far above us for its harmony to touch our souls. A great silence, like an impenetrable wall, shrouds its life from our understanding. White, therefore has this harmony of silence … it is not a dead silence, but one pregnant with possibilities.”

White is the sum of all colour, and yet is empty; white is unblemished and yet unfinished; white is innocence and also death. And for , one of the most thoughtful and assiduous artists of the postwar era, white is material. For almost six decades now, the american painter has worked largely with that single colour (or non-colour), which he deploys with countless variations of shade, brushwork, framing and support. Twenty-two of his paintings are now on view in a pithy exhibition at the dia art foundation’s gallery in new york, and it’s an event. Ryman has not had a new york museum show since his moma outing in 1993 (“”, according to critic roberta smith)

More conspicuously, this is the first show that dia has mounted in chelsea since the dreadful decision to sell the institution’s old home across 22nd street. In 2004, a year after opening its grandly impassive outpost in , on the hudson river, the dia ended up closing its original chelsea home (which now seems set for ). The closure was supposed to be temporary, but after a decade in the wilderness, we have a proper homecoming.

Ryman took an unexpected path to one of the sternest and most consistent careers in postwar american painting. He was born in tennessee in 1930, and after a stint in the army, he came to new york to play the saxophone. He got a day job at moma as a security guard, and seven years later he was still there – looking, learning, and making friends with dan flavin, sol lewitt and other artists in the confraternity that the dia went on to beatify in beacon. His earliest paintings here, done with caked impasto, date from when he was still on the security staff. There’s a pair of icon-like squares, one of which is closer to light grey than white, and interrupted by shafts of black and red. Then come two luxurious paintings, both from 1962, composed of white squiggles underpainted with cadmium or dark blue.

Those early paintings help unwind one of the worst misapprehensions of ryman: that his art is about nothing, and that his white-on-white works are nihilistic “last paintings”. Quite the opposite, really. As this exhibition deftly validates, the constraint of colourlessness has offered ryman tremendous freedom. White isn’t a subject matter, but an apparatus by which ryman rethinks how a painting is assembled, how it gains meaning, and how earlier explorations can be later redeployed and remixed. The paint can be slathered evenly, without evident brushwork, or else applied with more expressionistic swagger. It can be oil or acrylic, casein or a hard, pigmented resin known as enamelac. The achromatic surfaces also allow ryman to emphasize many different supports and means of display. We see him move from canvas and linen to more industrial materials, such as plexiglas and copper, on which the paint appears more emulsified; in many cases, he leaves a fraction of the paintings incomplete, to advertise what lies beneath.

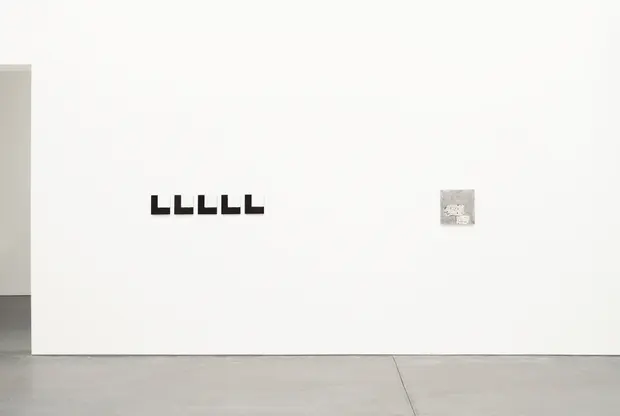

We see him try variegated, at times wild display methods. Factor, from 1983, stands freely in front of the wall, while pair navigation, from the year after and painted on fiberglass, is actually suspended above the ground with aluminum fasteners. Even the means by which ryman hangs his paintings – sometimes with aluminum bands, sometimes with screws, sometimes with tape – becomes an artistic act. He is the only artist who can thrill you with his use of staples.

The only truly white thing in this universe is light. But even white light is actually polychromatic, and ryman’s whites bristle with other colours, often toward the cooler and more metallic end of the spectrum. In a masterpiece – no other word will do – from around 1960, icy blue underpainting recalls the snow in , and the strokes tumble down from the top left corner into a beige void. The pigment in a smaller work from the same year is nearly green, daubed in an irregular quadrilateral on an untreated and unstretched piece of linen, as matter-of-fact as the face of jesus on the shroud of turin. A larger painting sees white transform from a romantic near-teal to a sallow, more stifling tone. They open up if you give them time, though really, it’s worth making multiple visits to this show to see the paintings in different light environments. I went three times – in sunny conditions, cloudy ones, and then (against the rules) at night – and each time was a different show.

This is not a ryman retrospective: there are only 22 works, dating from 1958 to 1985. And it’s not a temple, either. Courtney j martin, the show’s curator, has installed these paintings with real wit, in complementary or discordant pairs or threesomes. The variations in scale and format on a single wall allow you to see ryman’s art as more than just minimalist études, but full-blast artworks. Ryman’s paintings are abstemious, yes, but they’re remarkably warm. They are works of art in which the immaterial is made manifest.

Other, major works of ryman’s remain on view at the dia’s giant outpost in beacon, 90 minutes north of new york – still, as always, worth a visit. But jessica morgan, the former tate modern curator who became dia’s new director this year, deserves a round of applause for bringing the museum back to manhattan. I would be happy if morgan, who before her arrival in new york was an eloquent advocate for non-western modernism and for figurative painting, began in these coming years to push the dia a bit beyond its core competencies of minimalism and conceptualism, mostly from the us and germany. For now, we should be grateful for the dia’s repatriation – and to ryman’s contribution to an unseasonably balmy new york of a white christmas.